THE NANTES-BRESTCANAL

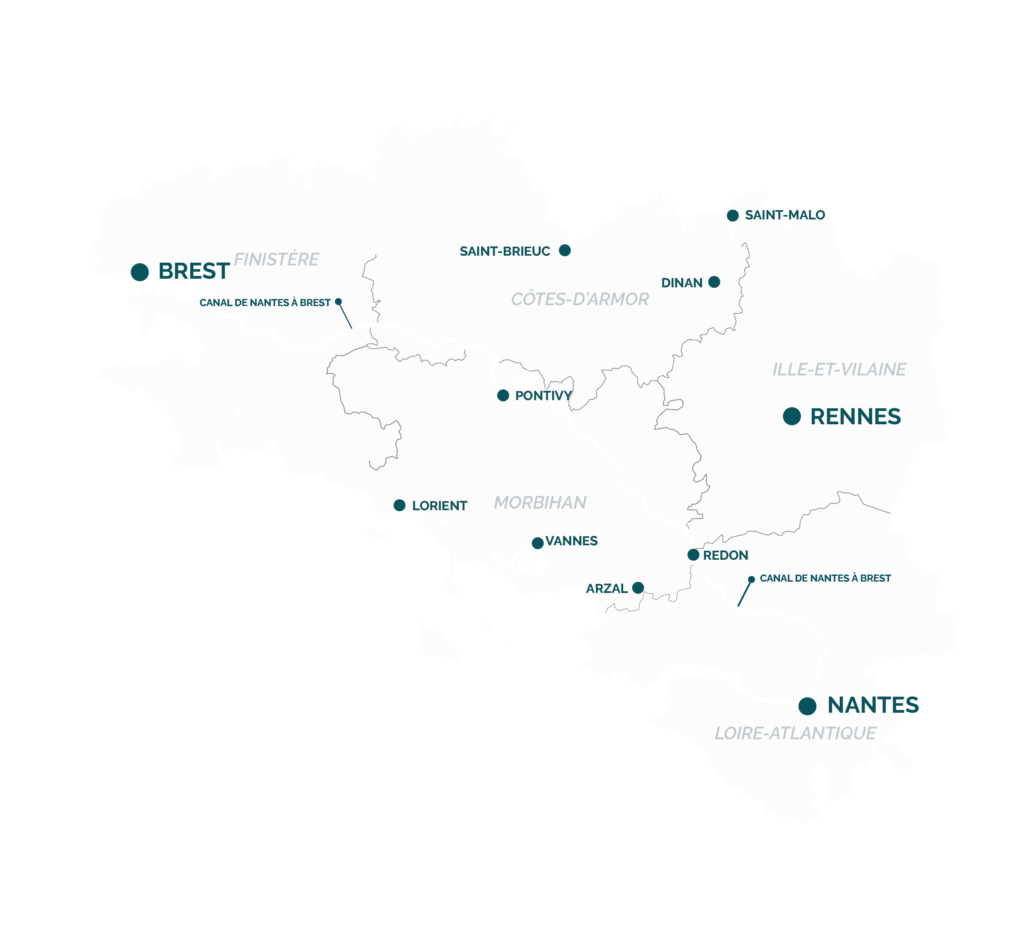

Running transversally from Nantes, city of the Dukes, in the south-east to the largest Breton port, Brest, in the northwest, the traveller will discover the heart of rural Brittany.

THE ROUTE

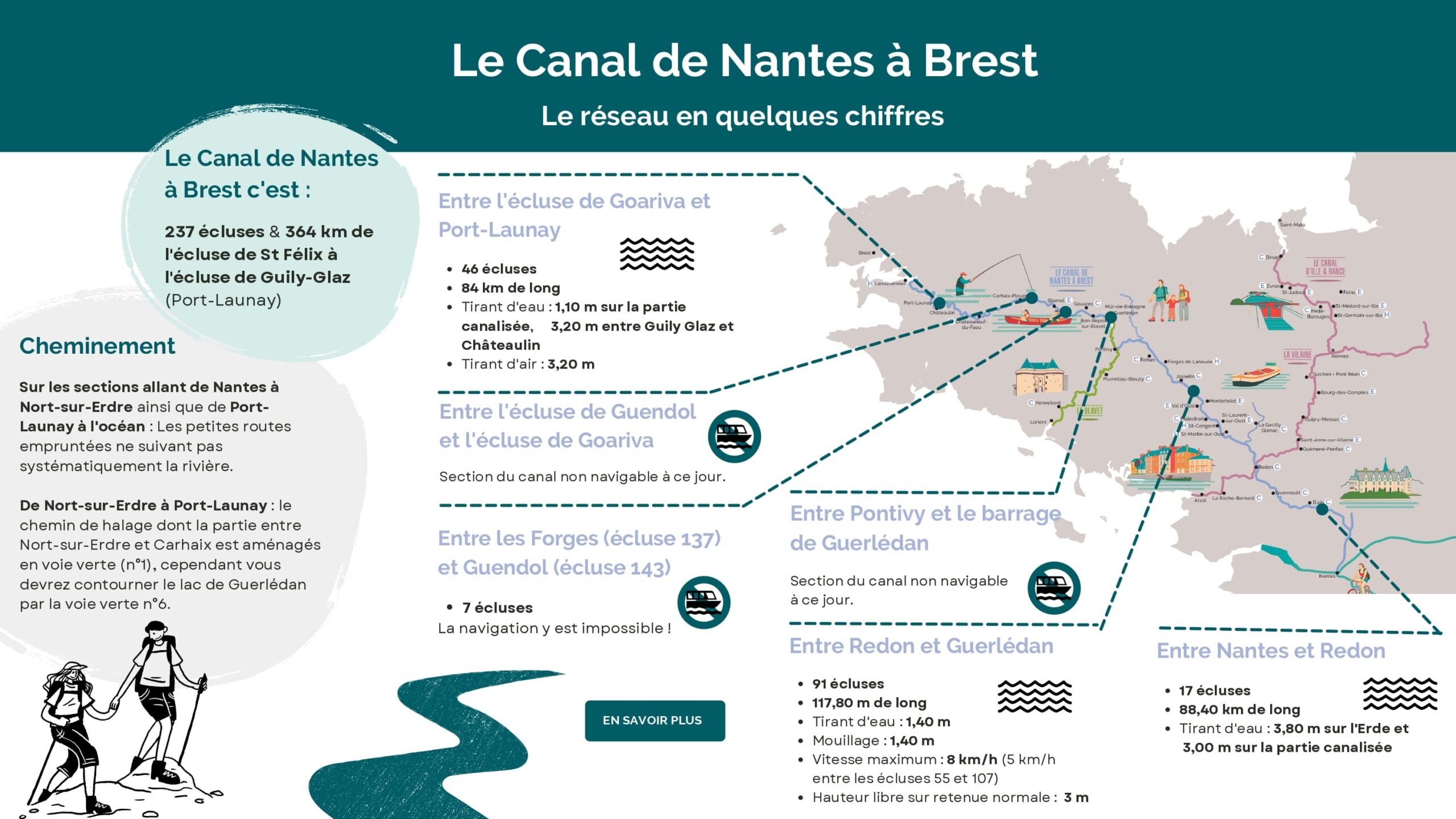

37 locks I 364 km from the St Félix lock in Nantes to the Guily-Glaz lock at Port-Launay. The Itinerary • From Nantes to Nort-sur-Erdre : There is no towpath so the route uses on minor roads that don’t always follow the course of the river directly. • From Nort-sur-Erdre to Port-Launay : The towpath runs from Nort-sur-Erdre to Port-Launay. The section between Nort-sur-Erdre and Carhaix constitutes Greenway n°1. Where the Guerlédan dam cuts the canal, you can bypass the lake by taking the Greenway n°6. • From Port-Launay to the sea : Similarly, there is no towpath, so the itinerary follows small roads that don’t always follow the course of the river.

BETWEEN NANTES AND REDON

17 locks I 88.40 km Draught : 1.20m on the Erdre and the canalised section Headroom : 3.80m on the Erdre and 3.00m on the canalised section

BETWEEN REDON AND GUERLÉDAN

91 locks I 117.80 km Draught : 1,40m Anchorage : 1,40m Maximum speed : 8 kph (5 kph between locks 55 and 107) HHeadroom : 3m

BETWEEN PONTIVY AND GUERLÉDAN DAM

Not currently navigable.

BETWEEN GUERLÉDAN LAKE AND COAT NATOUS DOUBLE LOCK

10 locks I 26 km Draught : 1,10m Headroom : 3,20m

BETWEEN THE DOUBLE LOCK OF COAT NATOUS AND THE LOCK OF GOARIVA

Not currently navigable.

BETWEEN GOARIVA LOCK AND PORT-LAUNAY

46 locks I 84 km Draught : 1.10m on the canalized part and 3.20 between Guily Glaz and Châteaulin Headroom : 3,20m

A little history

Central Brittany was once known as the "Siberia of Brittany". As early as 1627, a project to open up the area by connecting Brest to Carhaix was proposed. In 1745, Count François Joseph de Kersauson took on the project, however, it was abandoned for lack of funding. Only when the Inland Waterways Commission was set up in 1783 was the first serious project to link Nantes and Brest proposed.

A gargantuan project

Notwithstanding the report of the Commission, another 20 years would elapse before construction began under the Emperor Napoleon 1st. Napoleon’s rationale was both strategic and economic. The resumption of hostilities in the early 19th century led the English to blockade the principal seaports. The Emperor decided to establish an inland route to supply the arsenals of Brest and Lorient by creating a canal that linked them to the Loire via the Erdre in Nantes. From an economic viewpoint, commercial exchanges were difficult due to a rudimentary and poorly maintained road network.

The project was enormous. It was necessary to connect the river basins of the Loire, the Vilaine, the Blavet and the Aulne, and eight rivers: the Erdre, the Isac, the Oust, the Blavet, the Kergoat, the Doré, the Hyères and the Aulne. This in turn necessitated the creation of three summit reservoirs (dividing pounds) at Bout-de-Bois near Blain (19.83m), Hilvern, near Pontivy, (128.71m) and Glomel, near Rostrenen (183.85m). In all, the canal needed 236 locks over a length of 360 km. The workforce was drawn in part from the local population, who in a time of poverty desperately needed the work, but supplemented by prisoners of war, deserters and convicts from Brest. Men, women and children worked on the project for years. Eyewitness accounts tell us that the pay was derisory and the living conditions deplorable.

Napoleon I died in May 1821, so he never saw the success of his project. The canal opened in stages: 1836 for the Nantes to Redon and Carhaix to Brest sections, 1842 from Nantes to Brest, and finally concluding with the Oust derivation at Redon in 1854.

The canals became a major asset in the development of Brittany. Barges transported goods between the interior and the coastal ports, so developing trade. What had been intended as a military asset became a vital commercial artery.

However, even as the last section was completed, the canal’s future was already threatened, first by the development of the railways in the second half of the 19th century and then by road transport in the early 20th century. Commercial traffic slowly began to decline. The death knell sounded in 1930 when the hydro-electric dam at Guerlédan, north of Pontivy, cut the canal in two. The promised boatlift never materialised, making navigation between Nantes and Brest impossible.

For decades the canal seemed doomed until around thirty years ago when its value as a tourist attraction was recognised. Once more it is driving a new economic, environmental and social dynamic.