Manche-Océan canal

MANCHE-OCÉANCANAL

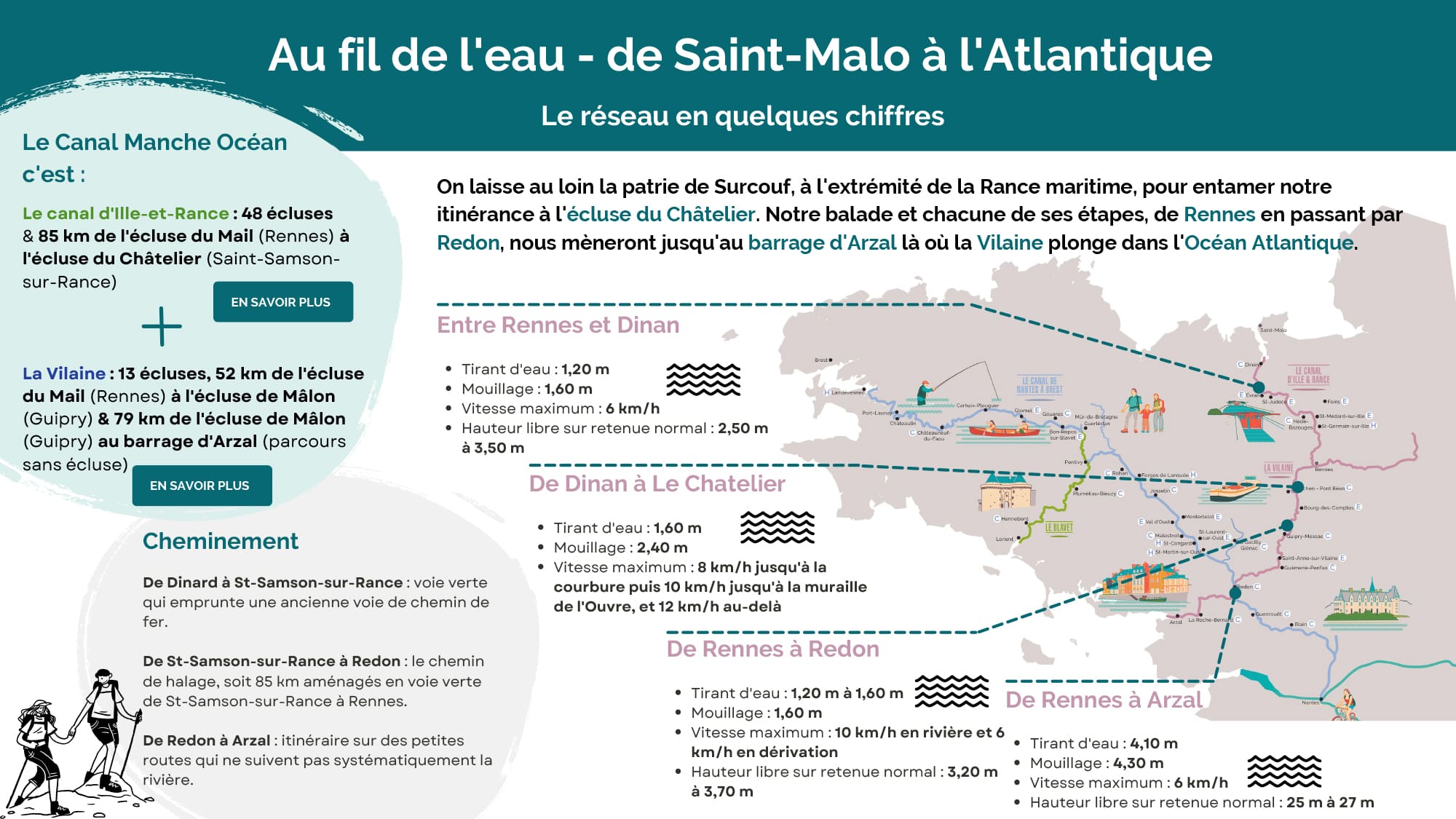

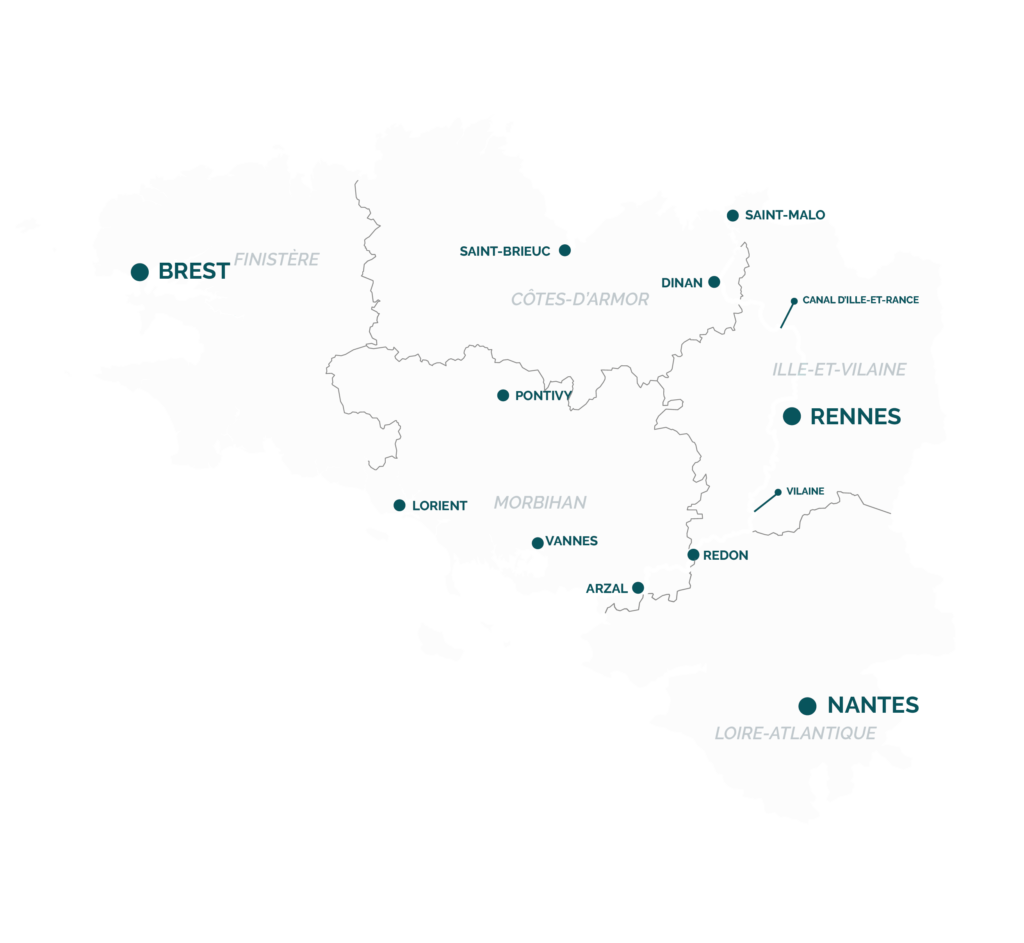

The Manche-Océan canal will take you from Saint-Malo in the English Channel to the Atlantic at Arzal. The journey starts from the Rance estuary, leaving St. Malo (the domain of the notorious privateer, Surcouf) behind you and joins the canal at the Châtelier lock. It will take you first to Rennes then on to the barrage at Arzal where the Vilaine meets the Atlantic ocean.

THE ROUTE

48 locks I 85 km from the Mail lock in Rennes to the Châtelier lock at Saint-Samson-sur-Rance

Rennes-Dinan section

Draught : 1.20m Anchorage : 1.60m Maximum speed : 6km/h Headroom generally : 2.50 m to 3.50 m

The Vilaine

13 locks 52 km from the Mail lock at Rennes to the Mâlon lock at Guipry 79 km from the Mâlon lock to the Arzal barrage (no locks on this section)

Rennes-Redon section

Draught : 1.20m to 1.60m Anchorage : 1.60m Maximum speed : 10km/h in river and 6km/h in diversion Headroom : 3.20 m to 3.70 m.

Rennes-Arzal section

Draught : 4.10m Anchorage : 4.30m Maximum speed : 6km/h Headroom generally : 25 m to 27 m.

A little history

The Manche-Océan canal uses the waters of three rivers: the Vilaine, the Ille and the Rance. It was developed over the centuries, starting with the Vilaine. The Vilaine was navigable from the Atlantic as far as Redon, a river-sea port in use as early as the 9th century. It is tidal as far as Messac. In 1539, François I authorised the town of Rennes to make the Vilaine navigable from Rennes to Messac, leading to the construction of the first ten locks between 1565 and 1585. In 1783 the States of Brittany – the Breton parliament – set up the Commission de Navigation Intérieure (Inland Navigation Commission) charged with managing all studies and projects for the development of Brittany's waterways. It was conceived under the “Ancien Régime” – the pre-Revolutionary system of government – initially for economic reasons in order to link Rennes, the provincial capital, to the seaports of Saint Malo, Brest, Lorient, Nantes and Redon. However, the plans were only implemented 20 years later for strategic reasons in order to circumvent the blockade of the channel and Atlantic ports by the English navy. Put on hold for some years, the work was resumed around 1816 for the original economic reasons. This was during the Restoration of the monarchy, but it was only completed 14 years later during the July Monarchy of 1830 in the reign of King Louis-Philippe I. Consequently, the Ille and Rance Canal, designed in 1784 and approved in December 1803, only opened to navigation in 1832. From then on, the inland waterways fleet grew across the whole canal network, transporting large quantities of goods and so driving the economic development of the interior. During the second half of the 19th century, the railways became a significant competitor, followed by road transport in the early 20th century. Commercial canal traffic began its slow decline. The waterways network seemed doomed until the 1960s when boating and other leisure activities started to grow. Today, Brittany’s rivers and canals are an integral part of its historical, architectural, environmental and touristic heritage, performing a vital role in regional development.